Overview

Research and

Collections Consulted

Early Mining Era

1850s to 1920

Michigan Tech & the Student

Experience 1930-1990

Personal Stories of Note

ks |

Personal Stories of Note - The Richey Family |

Appleton R. Richey Senior:

Appleton R. Richey (often referred to as “A.R. Richey” or “A. R. Richie”) was born in Dresden, Ontario, Canada, on January 8, 1845, and lived in Houghton, Michigan from approximately 1867 until his death in 1896. He was a well-respected and beloved citizen of Houghton, Michigan, and operated his own barbershop for most of his life.

He died in Houghton on August 2, 1896, after having suffered from a combination of undisclosed illnesses for over 3 years. He even sought relief for his maladies at Hot Springs, Arizona in December 1894, implying that he had considerable financial means at his disposal. His funeral was held at Grace Methodist Episcopal Church in Houghton (Portage Lake Mining Gazette, 8-06-1896), suggesting he was perhaps a member of that congregation or had friends who were. He was buried at Forest Hill cemetery. Today, there is no trace of his headstone on the cemetery grounds.

The death notice appearing in the August 3, 1896 issue of the Copper Country Evening News, described him as “One of Houghton’s oldest residents”. The August 6, 1896 issue of the Portage Lake Mining Gazette, reports that he lived in Port Huron, Michigan for ten years, after leaving his hometown of Dresden, Ontario (only 25 miles south of Port Huron), and then sailed the Great Lakes for one season.

Canadian census data suggests that Richey, at the age of 18, still lived in or around Dresden, Ontario, and the 1870 U. S. Federal Census sees him already residing in Houghton. The earliest record of his presence here is a newspaper advertisement for his barber salon in the Mining Gazette from February 1867. |

Richey allegedly learned the barber trade in Marquette before moving to Houghton. He must have been cooperating closely with his brother Josh N. Richey, who apparently was already established as the premier barber in Houghton (Figure 15).

An ad in the Mining Gazette from May 16th 1867 announces the opening of a Barbering and Hairdressing Shop by A. R. Richey, located on Isle Royale Street, opposite the First National Bank (putting it on the east side of lower Isle Royale Street, between what were then called Shelden Street and Lake Street). It explicitly lists cutting and dressing of ladies’ hair as one of his specialties.

An advertisement in the Mining Gazette (Figure 6), lists them as jointly operating “shaving, hairdressing and bathing rooms” under Shelden & Shaffer’s Drug Store on Isle Royale Street. That same year, the brothers added some new services to their operation, including the cleaning and repair of clothing, according to a 06-24-1869 article in the Gazette.

J. N Richey probably left Houghton sometime around 1870, presumably for Minnesota (where he later appears in Duluth according to the 1910 and 1920 census), and thus leaves A. R. as sole proprietor of their business. |

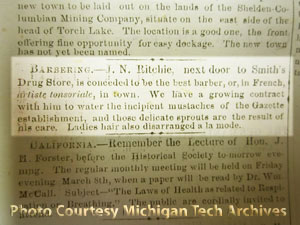

Figure 15

Newspaper tidbit from the 02-28-1867 Portage Lake Mining Gazette, extolling J. N. Richey’s skills as a barber.

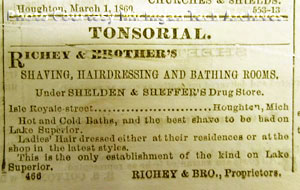

Figure 6

Newspaper advertisement for Richey & Brother’s (Portage Lake Mining Gazette, 04-29-1869).

|

In the 1870 census A. R. Richey is listed as a “mulatto” barber with a personal estate of $800 living in Portage Township with his mulatto wife Hannah and infant son Charles. As researchers, it is reasonable to wonder what the mulatto designation implies about their ancestry. Richey employed a black barber named Robert Booker (born in Michigan circa 1848), who also lived with them. A 48 year old mulatto woman named Elisabeth Jeffrey, and a 14 year old white boy, Caspar Brandt, round out the household. The boy’s occupation is given as “clerk in store”, so perhaps he worked in the barber shop as well, handling payments and keeping the shop clean. The makeup of the household is quite different by 1880, with Appleton being widowed, and three young daughters living with him. No trace of the son, Charles, or any of his previous housemates (Robert Booker might have left the area after being wrongfully charged in a burglary case).

In the 1887/1888 Holland’s Handbook and Guide, Appleton is listed as A. R. Richie [sic] working as barber at 603 Shelden, and residing at 727 Shelden (note that the addresses listed in these community listings don’t correspond to the numbering scheme in the Sanborn insurance maps for the same period, so precise geographical locations are difficult to ascertain). We can identify the 702 address, because he paid property taxes for Lot 13 of Block 1 (and the house thereon) in Houghton from 1873 through 1896 (his name is spelled variously, for instance he is A. R. Richey in 1873, but the name is rendered “A. R. Richie” in the 1890 tax roll). He must have purchased the property from Ransom Shelden right around 1873, because it is listed with this famous citizen’s numerous properties, with Appleton’s name added in pencil in the 1873 tax roll ledger. This house was likely his home only, and not ever the location of any of his businesses. In 1873 the property was assessed at a value of $340, and he paid $16.40 in total taxes. The strength of the dollar fluctuated greatly over the following decades, and around the time of his death in 1896 the property value was only $200, for which he then paid a little over $6 in taxes every year.

The 1895-96 Polk & Co Directory for Houghton County lists it as on the north side of Shelden Street, 2 houses west of Franklin Street, near the modern-day NW corner of Shelden Avenue and Franklin Street, where the Krist filling station is now located (824 Shelden Ave., covering historic lots 13 and 14). His barber business eventually operated out of the new “bank building” (i. e. what was at the time the “National Bank of Houghton” (Figures 16, 17) on the NE corner of Shelden and Isle Royale Streets, now the downtown Wells-Fargo Bank), after it was completed in 1888. According to the Portage Lake Mining Gazette, A. R. undertook an extensive trip “to the principal cities east” downstate in the summer of 1890 to further his knowledge of newest trends in the barber profession (PLMG, 08-14-1890; 08-21-1890).

Figure 16

MS042-042-999-T-350: View of the Dee/Shelden building with McConnell’s liquor and tobacco store and a drug store, as well as the new Houghton National Bank with a barber pole and the entrance to Richey’s barber shop clearly visible on the Isle Royale side of bank building; dated 1911, but should be from before 1900.

Figure 17

MTU Neg 00269: Shot of the bank building, again with the barber pole and entrance to the barber shop in the basement visible; must be from between 1888 and early 1890s.

Appleton seems to have been a prolific entrepreneur, and in addition to running the barber shop, he also delved into other business ventures over time. In June 1869 he and his brother began accepting laundry to wash and clean at their barber shop. In July of 1869 he bought out the fruit and vegetable stand of William Jackson and turned it into a successful grocery and provisions store, by switching to fresh, locally grown produce and a great variety of canned goods. The variety of goods retailed there seems to have expanded seasonally. An advertisement in the December 9, 1869 Portage Lake Mining Gazette list fancy candy and Christmas toys among the wares. The address of this business is given as opposite the first national bank. In 1871 he identified a crucial market gap and added a restaurant in the rear of his barber shop, as there was “no other eating-house in town” at the time. “Fresh oysters, chickens, game, etc.” were to be served at all hours, whenever procurable. As with all his ventures, this restaurant soon was expanded as well, and transformed into a “first class restaurant on the European plan” in a new location in the former Dallmeyer building in 1873. He hired a chef from Chicago, a Mr. Henry Gale, and left the day to day operations to a manager, Mr. William Black. Day boarders were to be accommodated as well, “at reasonable rates” (PLMG 12-04-1873). In 1872 he opened a news depot in connection with his barber business, providing customers with daily papers from Chicago, New York and Detroit. In 1880 he made “teaming and draying” another business he got involved with, and henceforth provided for the transportation of baggage to and from the boat docks (PLMG 5-27-1880), and in 1890 he took over the Troy laundry from Charles R. Orth, expanding on his previous experience with the laundry business (PLMG 08-21-1890).

Sarah Rickman Richey and Offspring:

Appleton R. Richey’s first wife Hannah (nee Paris) died in 1879, only ten years after their wedding (PLMG 08-06-1896). Accordingly, Appleton is listed as a widower in the 1880 census. However, very shortly after, he married a Mrs. Sarah A. Rickman of Dresden, Ontario (born 1846, possibly in Ohio) on Aug. 7th 1880 (PLMG 10-14-1880) in Dresden. Appleton clearly kept a connection to his old home town, as he found his new bride there. Sarah Rickman likely arrived in that part of Canada sometime before 1860, and was clearly a widow when she married Appleton. The Canadian Census of 1871 lists a Sarah A. Rickman (*1846 in U. S.) in Chatham, Ontario. Sarah’s nationality is given as African, her religion as Baptist, and she apparently was married to Thomas Rickman (*1836 in U. S., married, African, Baptist). They had two children: Malecca (*1863 in Ontario, African, Baptist), and James (*1868 in Ontario, African, Baptist) at the time. Sarah is attested to be an Ohio native, and her maiden name is given as Mccackle in the marriage record for Edward T. Rickman, and another son from that first marriage (born 1875), who would later join his mother in Houghton, Michigan.

Sarah Richey remained at the Shelden Avenue family home in Houghton until after 1908, according to testimony given by her daughter in law, Bessie Richey, in 1911 divorce proceedings. The 1910 census sees her living in Marquette, however. The 1900 and 1920 census lists an African American named James Rickman (born 1868 or 1869 in Canada) in Marquette. This is clearly her son James from her first marriage. According to Northern Roots he came to Marquette in 1886, and worked there as a barber, and the Michigan Manual of Freedman’s Progress lists James Rickman as a property owner there in 1915 (page 214). His wife was Jessie Amalia Williams Rickman, and they had four children according to Northern Roots: Blanche N. Rickman Matthews, Ruth Elizabeth Rickman Hobson, James Albert Rickman, and Helen Louise Rickman Grant. Two of these Rickman children would later become educators in the Upper Peninsula. Blanche taught at the Republic Schools in 1917/18, and James junior, known as “Jack”, studied to become a teacher at Northern State Normal School (now Northern Michigan University), and later worked at the school on Neebish Island near Sault Ste. Marie, among other places. Sarah Rickman must have died while living with her son’s family in Marquette, sometime between 1910 and 1920. |

Appleton R. Richey Junior:

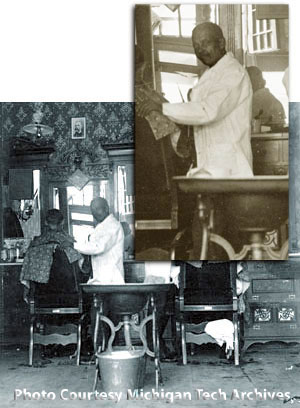

Appleton R. Richey, Junior was born in February 1874 in Houghton to A. R. Senior and his first wife Hannah. In the 1895/96 Polk Directory he is listed as living with his father and also working as a barber for him. He took over the business after his father’s death, as the Houghton Polk directories for 1897/98 1899/1900 list Appleton junior as the barber operating the shop in the basement of the National Bank building, and living in the Richey house on Shelden, two houses west of Franklin Street. In 1900 A. R. junior married Adeline E. Thomas (*1871 in Canada) in Houghton. She might very well be from Appleton senior’s old stomping grounds in the Dresden area. The 1901/02 and 1903/1904 Polk directories give A. R. and Adeline’s address at his parents’ house, but the couple might have had separate quarters in the rear (“r”) of the building. He is still listed as working as a barber in the bank building. There is a possibility that A. R. Richey junior is the African American barber seen in Figure 5b, as his physical appearance and circumstantial evidence captured in the photograph match Appleton’s available biographical information. The photograph should be from about 1910 or slightly later. |

Figure 5b

Figure 5b

|

The 1910 census still lists A. R. junior and his wife as Apleton [sic] and Addie E. Richey, living in Portage Twp. (Houghton). No children listed. In 1912 he is still working as a barber at 49 Isle Royale Street, but by 1916/17 there is no mention of him in the Polk. A photograph from around the end of WWI in late 1918 (Figure 18) shows a telegraph office in the place of the former barber shop (the barber pole is gone too), and the 1928 Sanborn plat still places the telegraph office in that same location. This strongly suggests that he must have left the area before 1918. In any event, by the 1920 census they are no longer in Michigan, and in 1930 and 1940 Appleton seems to be living in Los Angeles, California, with no trace of his wife Addie. If this is indeed the same person, he may have remarried, as there is a Lena Richey (born 1875 in Missouri) living with him (unless Lena is a corruption of Adeline, and her birthdate and home country were also misreported).

Figure 18

MS042-063-999-Z617: View of the bank building from around the end of WWI in late 1918 (note French, Japanese and British flags above 2nd window from the right on 2nd floor) shows a telegraph office in the place of the former barber shop. The barber pole is gone too.

However, the possibility exists that Appleton junior died sometime around 1911/1912 in Houghton. There was a hearing concerning the appointment of an administrator concerning the estate of Appleton R. Richey at the probate court in October 1912. It is not clear if this concerns the estate of the elder Appleton, or that of his son. If Appleton Junior was still alive then, why did it take so long to execute his father’s will? Was this perhaps related to Sarah Richey’s death, or A. R. junior’s desire to pack up and leave Houghton? Curiously, The Block 1, Lot 13 property is listed as “A. R. Richey Estate” in local tax rolls from 1911 through 1917. Taxes were paid promptly, indicating that A. R. junior or another family member was still residing there. In the 1918 tax roll, the line “A. R. Richey Estate” is crossed out with pencil and replaced with John J. Ruelle, who also owned the neighboring property. Appleton, or his brothers, if he was already deceased, must have sold the family property sometime in 1917 or early 1918. This corroborates that the last members of the Richey Family must have left Houghton right around that time.

Appleton’s Granddaughter Florence Bennett and Her Family:

An illustration of how African American settlers in the Keweenaw were able to break into new career fields is the story of Appleton Richey’s granddaughter Florence Bennett, and her husband Paul “Osby” Wood. According to an announcement in the Daily Mining Gazette from December 28, 1910, Florence Bennett, daughter to Cora Bennett (nee Richey) and L. M. Bennett, married Osby Wood on December 27, 1910. The wedding took place at the St. Ignatius Catholic Church rectory in Houghton. The Daily Mining Gazette notes that both were “colored” and details Miss Bennett’s background as having graduated from the commercial department of Houghton High School and having briefly worked as a stenographer in the office of the Houghton County Fair. This is confirmed by the Polk directory for 1910, where she is said to work as a stenographer for J. T. McNamara, who was the secretary of the Houghton County Agricultural Society, and the manager of the Amphidrome around then. At the time of the wedding she was a bookkeeper at the Markham Candy Company. |

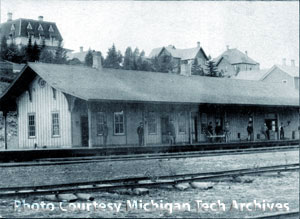

Figure 19

Figure 19

MS044-003-001-001: Picture of the Duluth, South Shore and Atlantic Railroad depot in Houghton around 1900. We know of two African American individuals who worked in the dining car of this rail line: Cornelius Richey and Osby Wood. |

Mr. Wood was a chef in the dining car of the Duluth, South Shore, and Atlantic Railroad (Figure19). The paper actually used “chef” instead of cook, which perhaps was meant to indicate that he had some type of formal culinary training or maybe supervised other kitchen staff. Interestingly, Florence’s uncle Cornelius Richey (a son of A.R. and Sarah Richey) was also working as a cook on the railroads at the same time. Florence and Osby went on a several week honeymoon in Chicago, and made their home at 6 Shelden Street in Houghton (The Calumet News, 12-27-1910), which should be the old Richey residence, where her Uncle Appleton junior also lived.

They moved to Escanaba sometime after, as the Polk directory does not mention them in 1912, and in 1920 Florence Wood (*1893) and Paul Wood (*1880) as well as their two year old son named Osby, and two year old daughter Cora (after Florence’s mother) are living in Delta County. Florence’s Aunt Louise Bennett (*1907 in MI) and Uncle Fred Bennett are also living there. According to Northern Roots, the younger Osby Wood was born in Escanaba in 1918, putting their arrival there before that date. In 1930 the Wood family is recorded in Chicago, IL. Their additional children are Jeannette, Paul, Fred, and Mary. Louise and Fred Bennett have moved with them. They are still there in 1940. In Northern Roots we learn about the later exploits of Osby Wood junior. He too became a railroad cook, which eventually brought him back to the Upper Peninsula. He was a resident of Michigamme, where he was involved in local sports, before opening a restaurant in Marquette. In 1940 he is once more found in Chicago with his parents, according to census data, and in 1942 he enlisted into the U.S. Army to fight in WWII.

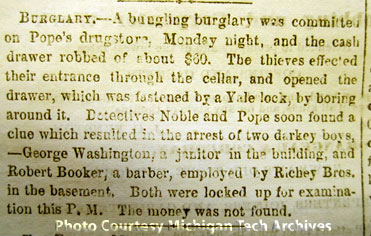

Figure 20

Figure 20

News article detailing the burglary at Pope’s drugstore (Portage Lake Mining Gazette, 06-30-1870). |

Robert Booker and George Washington:

A criminal case from 1870 illuminates some of the conflicting attitudes African American citizens faced in the Copper Country community at the time. On the night of June 27, 1870 Pope’s Drug Store in Houghton was burglarized. This drug store occupied the same building that the Richey brothers were operating their barber shop out of, with the drug store being on the upper level, and the barber shop in the basement. The thieves gained access through the basement barber shop, by breaking open the door blocking the passage to the store. Between $50 and $70 (the amounts vary by account) was stolen from the locked cash drawer that had been forced open with a chisel of some sort. Suspicion fell upon two black men affiliated with the building. One of the suspects, Robert Booker was a barber employed by the Richey brothers, while the other suspect was George Washington, a janitor in the same building, who Booker was friendly with. Whenever the papers refer to the Richey brothers, who were established businessmen of considerable financial means, the language is respectful and complimenting, but in the burglary case the two suspects are dismissively referred to as “darkey boys” by the Portage Lake Mining Gazette (see Figure 20), showing a condescending and rascist tone, that apparently could come to the surface in situations when the black individuals concerned were not insulated by some financial means and personal connections. |

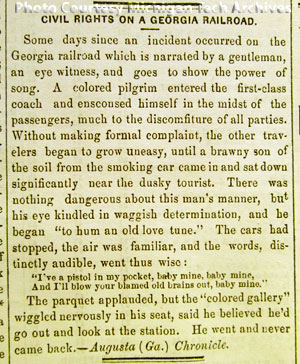

Figure 21

Figure 21

“Humorous” anecdotal story, picked up by the Portage Lake Mining Gazette on 02-19-1880. |

Another illustration of the unsettlingly racist attitudes that were at times espoused by the editors of the local papers is their running of a brief anecdote alleged to have occurred in Georgia, and apparently intended to be humorous to local readers under the heading of “Civil Rights on a Georgia railroad” (PLMG 02-19-1880, see Figure 21).

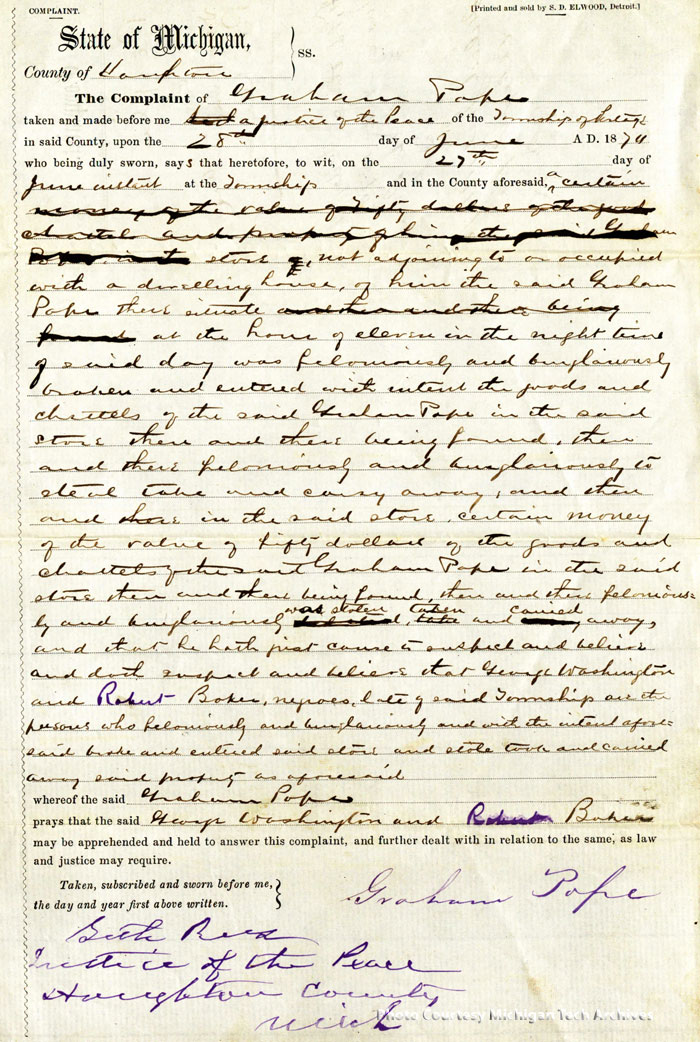

Court records for the burglary case (see Figure 22) show that both suspects were arrested on warrant on June 28 and arraigned in the Houghton County Circuit Court on June 29. Unable to post the bail of $300, they were both lodged in the county jail. There is some indication that fingers were pointed at the most convenient suspects in the case. A somewhat concerning fact is that one of the arresting law officers, and the court clerk were both members of the Pope family, which was one of the wealthiest and most influential business families in Houghton at the time (see Polk directory listings). According to witness accounts, all links between Washington and the break in were circumstantial, and primarily based on his living in the building. Booker was linked due to his friendship with Washington and the fact that he had access to the barber shop. Interestingly, Caspar Brandt, a white boy also working for Richey, seems to have been friendly with both suspects, and was seen with them the morning after the break-in. As far as we known he was never bothered or questioned in any way in connection with the case. The main piece of evidence was a coat belonging to George Washington, which had white markings, shown to be caused by a powdery substance identified to be carbonate of lime. The powder was chemically identical to the marble dust stored in a barrel near the passage between the barber shop and the drug store upstairs, and some of it was found on the ground under the forced door. Washington’s seemingly suspicious behavior concerning the very same coat the morning after the burglary also contributed to his appearing guilty.

Figure 22

Original Complaint filed by Graham Pope concerning the break in at his drugstore, naming Booker and Washington as suspects.

|

Interestingly, A. R. Richey, Robert Booker’s employer, was one of the witnesses testifying on behalf of the defendants during a hearing on July 1. He mainly gave account of the potential whereabouts of the coat in question, which had been seen hanging in a shed on Richey’s property some days before the crime, and which Washington claimed to have only retrieved from there the morning after. As a result of the hearings, on July 2 the bail for George Washington was set at $500, and again unable to offer a sufficient amount, he was committed to the jail until the date of his trial. Robert Booker on the other hand, was released immediately (was this because he had a closer connection to Richey, who spoke up for him, or that the evidence against him was just too scarce?). Washington was tried in the Circuit Court beginning July 13, 1870 (Figure 23), and he was found “not guilty” by the jury on July 15th 1870. Nothing more is heard of either Booker or Washington after their respective releases from custody. Possibly they left the area, because of the impossibility of finding employment after being associated with the crime, despite being cleared of all charges.

Figure 23 >

Front of dust cover intended to protect the court documents filed in the criminal case against George Washington. |

|

| The personal stories pertaining to the Richey family are but one example of how a variety of primary sources can be investigated to piece together a narrative that adds depth and richness to established narratives about local history. African American social history in the Copper Country is a significant topic for research and discussion, one which will hopefully be more deeply explored by future researchers. |

| |

|